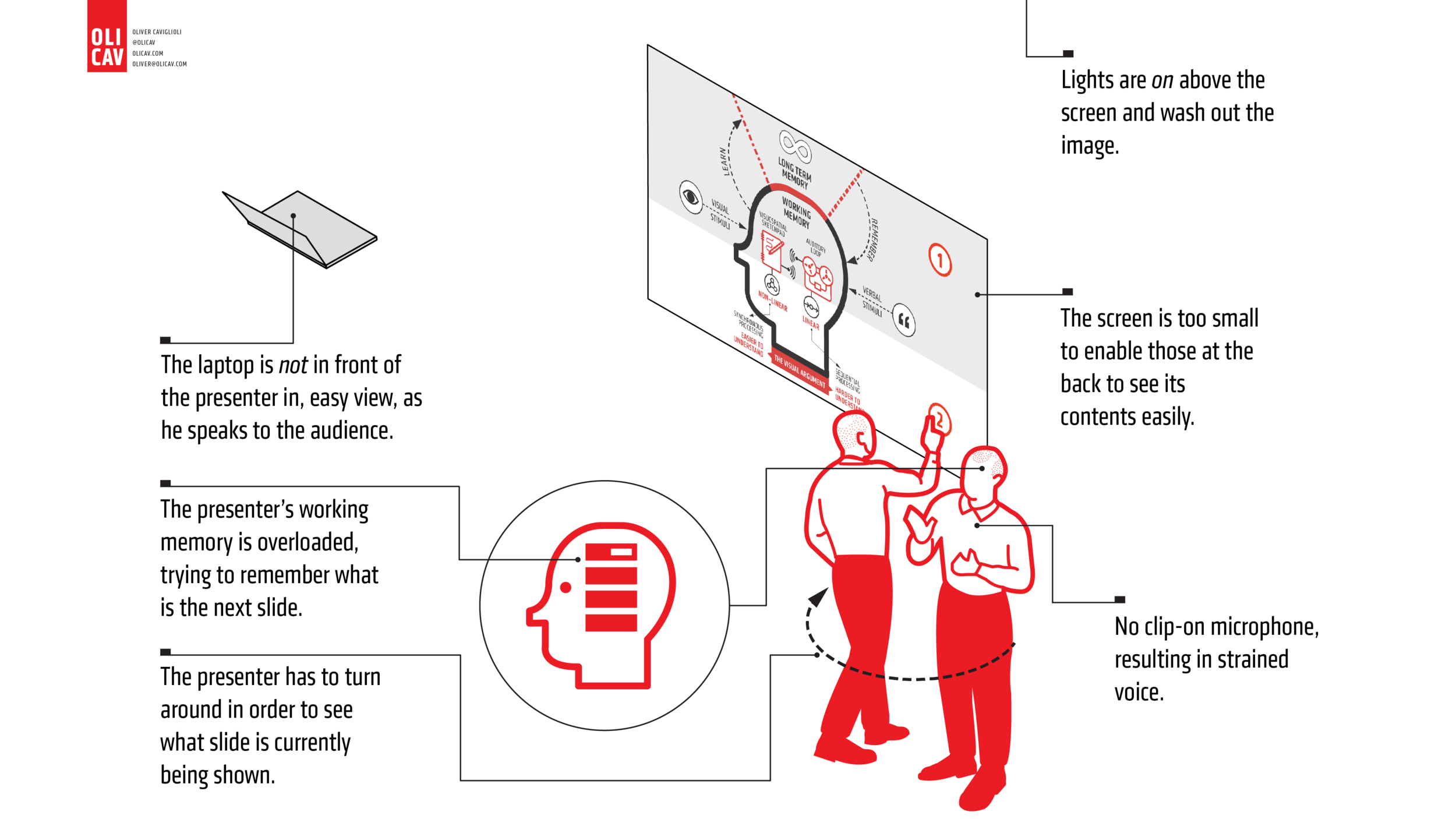

As we know from the study of effective teachers, it’s important not to overload working memory in order that the teacher can notice and respond to the reactions of his students. Similarly so with trainers. The conditions depicted below represent the worst collection for a trainer.

LIGHTS | Often — and this is entirely the fault of the architects — light strips run down the length, not across the width of the hall. Additionally, often there is no mechanism to switch individual lines of lights on or off. As a consequence, the trainer is faced with a dilemma. Either all the lights are on, in which case the projected image is washed out and barely visible and the audience is illuminated to aid their note taking. Or, the lights are off, leaving the image nice and clear but the audience in the dark, having problems with their note taking.

LAPTOP | With the laptop not in view of the presenter, he has to turn around and look at the screen in order to know which of his, sometimes 200+, slides is being projected. This is highly unsatisfactory to both presenter and audience. Equally — and insufficiently acknowledged — the presenter’s working memory is overloaded in the attempt to remember what his next slide will be. With over 200 slides, and involving many changes across different training events, this represents a serious challenge to the effectiveness of the presentation.

SCREEN | If the screen is too small for everybody on the back row to see its contents easily, without any strain, the whole presentation, or training day, is spoilt for many teachers. TV screens for classrooms are, quite clearly, far too small for training or presentation venues. Even within a classroom, for smaller events, the TV screen is often placed too low, resulting in the back row or two, having their view obscured by those in front.

MICROPHONE | No microphone for the trainer is a problem in larger venues. Hushed tones and subtle changed in tone are not possible at high volume. Even hand-held microphones are troublesome in restricting the presenter’s gestures.

Reversing these poor conditions, we can see what a venue that works well for its intended purpose looks like.

SCREEN | This is the ideal size — almost cinema-like dimensions. This needn’t cost any more money as an actual screen is not necessary. A blank white wall will do nicely. All that’s required is for the projector to be moved back away from this wall. Or the use of a modern projector with a wide ‘throw’.

LIGHTS | Being able to switch off the light, or row of lights, nearest the screen, allows it to be strongly and sharply illuminated, while leaving the audience in light necessary for their note-taking and other activities.

CLIP-ON MICROPHONE | Small and unobtrusive, the clip-on microphone helps the presenter forgot it’s there. Now, different tones and subtleties of voice and breath can be used, decreasing the sense of space between trainer and audience.

LAPTOP | Oh what a difference having a laptop easily in view, in front of the presenter makes to the ease and effectiveness of his presentation. The current slide, projected behind him, is immediately visible on the small laptop screen. No inelegant and unprofessional turning around is necessary. And, equally, significant, the next slide is also on view, eliminating the devotion of valuable and scare working memory resources to trying to remember what comes next.

CLOCK | Not present in the image above, a large clock on the back wall, behind the audience and directly in the sight of the trainer, makes time-keeping a cinch.